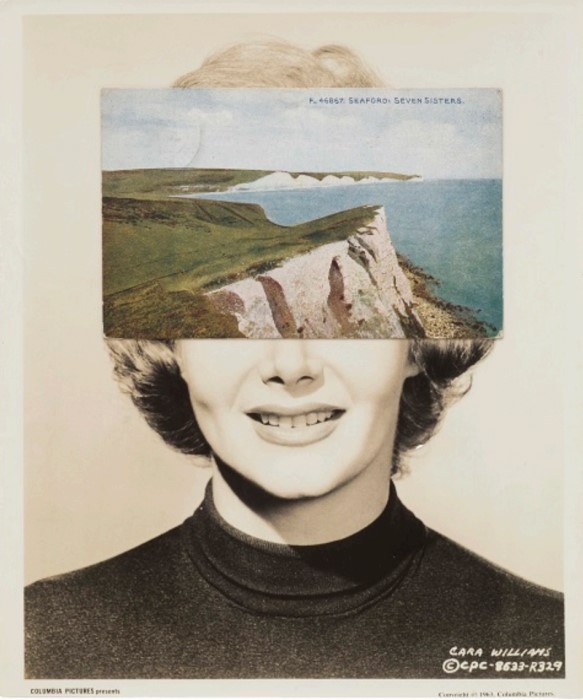

The Turner Prize comes to Sussex in 2023

News | Art

“The noise surrounding the rise of Classic Method English sparkling wines has been growing for a number of years. It’s now beyond doubt that these wines can hold their own in terms of quality and recognition both nationally and around the world.

It is certainly a challenge both as a winemaker and a business owner to produce world-class still wines in England’s marginal climate. In many ways the challenge here is greater than with sparkling wines.

For one thing, quality sparkling wines are made from grapes with high levels of acidity – levels that would be considered searingly sharp and unbalancing in still wines. Meanwhile, sparkling wines also have the luxury of time to evolve into greatness, over the course of an intricate winemaking process that can go on for five years or more.

But still, the blanket dismissal of still English wines overlooks the massive leaps in progress that have been made over the last couple of years alone. With the right weather, in the hands of the right winemakers, the same Chardonnay and Pinot Noir grapes so beloved by English sparkling wine producers can make truly excellent still wines.

The grapes require some favours along the way – a kind English summer, expert vineyard work, judicious grape selection at harvest and careful (often costly) winemaking techniques. With all of these factors in play, it is a certainty that in good years, some English vineyards will produce still Chardonnay and Pinot Noir wines that can stand proud on the world stage.

Yes, there’s a lot of hedging in that statement. And this is the question that greets every freshly opened bottle: How consistently can these wines be delivered? Given the vagaries of our climate and inevitable high prices consumers must pay for these small-batch wines, we remain in wait-and-see mode on the consistency question. Yet progress is being made with every vintage and some very promising contenders are emerging.

Pinot Noir could very well be the future star of English still wines. It’s now our most-planted grape variety, as it can be teased in different directions in the winery to make white, rosé or red still wines, as well as turning up in most styles of sparkling wine.

Could red English Pinots ever compete with Burgundy? Stop laughing at the back and open your mind to the possibilities presented by climate change and fast-improving understanding of English growing conditions. We’re already using Burgundian clones of Pinot Noir, which tend to ripen much earlier and make fruitier wines than vines originating in Champagne. In good years, when the grapes ripen well, winemakers are able to make all kinds of clever decisions in the winery to extract the best from them and produce crisp pale rosés and delicate, ethereal reds.

The last couple of years have seen a flurry of still Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays launched off the back of the bumper 2018 harvest. But even now, many producers continue to see Bacchus as the flagship for English still wines.

Unfamiliar with the name? The chances are you won’t be for long. Bacchus has a quintessential freshness and aromatic complexity that has led many to call it our answer to the behemoth that is New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. Plus the pleasing aptness and simplicity of the name alone makes Bacchus hard to dislike.

Winemakers love Bacchus for the endless scope it presents for experimentation. We can play with different yeasts, press the juice from the grapes in different ways, ferment at different temperatures, age it in oak… and end up with markedly different wines at every last branch of the decision tree. And there is so much scope for Bacchus to grow here – literally. Despite being the abundant ‘still’ wine grape in the UK, it still accounts for just 5% of plantings.

Once you’ve tried Bacchus, you’ll almost certainly want to come back to it. It’s our job to get things right on the supply side.

I’ve mentioned experimentation with Bacchus, but that’s not the half of it. The inquisitive minds behind the English wine revolution are leaving no stone unturned in their quest to present you with interesting new offerings. Experimentation continues daily with different grape varieties and winemaking techniques.

Ancient methods are being revived in pioneering new ways. White wines are being fermented ‘on their skins’ to extract tannins and texture, with the resulting skin-contact or orange wines occupying an intriguing space between regular white wines and light, dry fino sherries. Some of these wines are fermented in massive clay amphorae, just as they were thousands of years ago. Meanwhile yeasts cultivated in labs are increasingly eschewed as the engine of fermentation, with wild yeasts from the vineyard preferred for the unique characters they can lend to the finished wine.

This is happening in more places than you might expect, but the wines of Tillingham here in Sussex and Ancre Hill in South Wales are definitely worth a try if you want to see just how far the boundaries are being pushed in English still winemaking.

Without doubt, the pathway for English still wines is not as clearly defined as for sparkling wines. But as we continue to test, tinker and observe in our vineyards and wineries, the map is taking shape. We know more about what works, what doesn’t work and what might just work with every passing year, and the road ahead definitely looks an interesting one.

We hope you’ll join us on the journey.

Alison Nightingale is the owner and winemaker at Albourne Estate, an award-winning producer of still and sparkling wines and a Sussex Modern wine partner.

News | Art

Story | Art | Landscape | Wine

Story | Landscape

News

Art | Landscape

Art

Wine | Overnight | Accommodation | Landscape

News | Art

Overnight | Story